Amazing book alert! Author Elise Loehnen's On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins & The Price Women Pay for Being Good is a smart, personal, can't-put-it-down exploration of "the ancient rules women unwittingly follow in order to be considered 'good,' showing how this patriarchal dogma shapes women's lives while showing us another path through.

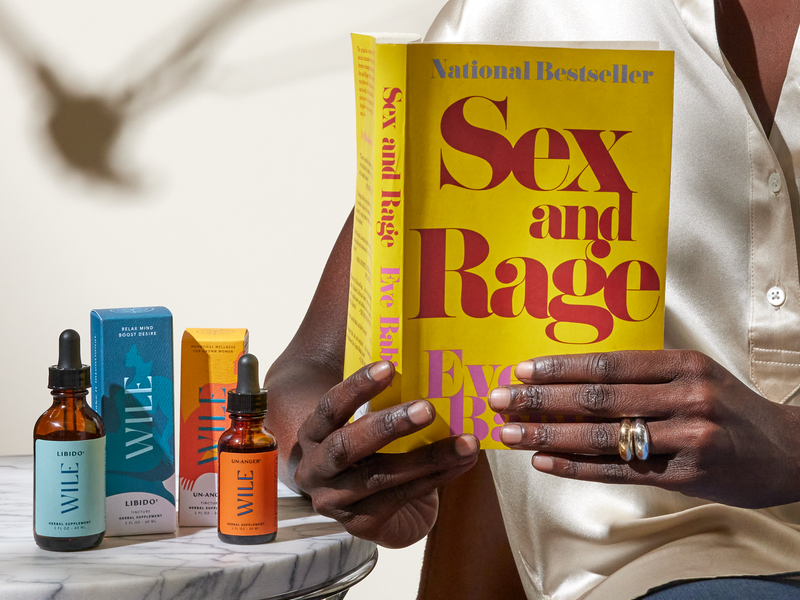

These two excerpts from Wrath were particularly interesting to us. Wile Un-Anger tincture is only product we know of that addresses this squelched human expression in women. Like Loehnen, we see anger as a useful emotional that can help us activate change and signal a need for boundaries and care.

OUR UNEXPRESSED NEEDS AND INTERNALIZED PROTEST

Censure for appearing visibly angry has deep roots: There is no realm, private or public, where women and girls get to work with their anger. We’ve been trained to make other people comfortable. We’ve been directed toward passivity and its implied dependency and victimhood. We’ve been instructed to suppress our natural aggression, or we’ve been told we shouldn’t have any at all.Because we cultivate no appropriate channels, this aggression finds its way out sideways. From childhood, we were not raised to acknowledge or understand our “bad” emotions. Nobody modeled proper exploration and expression or coached us in our feelings as we grew.

There are repercussions: We struggle to exist in discomfort without rushing to paper it over, to make everything OK. We are so eager for reassurance that we are worthy of love, that we are good. And for many of us, goodness has required obedience, compliance, softness, “femininity.”

We are taught that we are nurturers, limited to the domain of caring; we are taught that our first instinct when stressed is “tend and befriend,” rather than “fight or flight.”

It’s not possible to say whether our behavior is conditioned into us or truly “natu-

ral.” This training to focus on other people first is a heavy legacy,

implying that it is our mandate to put the emotional needs of

everyone else before our own, that prioritizing ourselves is a sign of

deviance. Good girls don’t fight, good girls don’t yell: We’re more

mature, more emotionally evolved.

I’m not buying it.

History, and our own lived experience, certainly tells us that it’s more complicated—and that caring for others and meeting our own needs should not be mutually exclusive. This radical revision would simply require reciprocity—a subtle restructuring of both relationship expectations and society itself, where women’s care is no longer taken by men to be a patriarchal right or foregone conclusion…

METABOLIZING OUR ANGER—AND MOVING PAST AFFIRMATION

Our resentment, frustration, and anger live in us. When our partners, our parents, our bosses, the system itself, refuse to absorb our wrath, to hear us, we don’t know where to put these bad feelings— and they must go somewhere. We shift into blaming and shaming. We become angry with ourselves and each other. And then, when we engage in the public sphere with our unrealized rage—the result of long-unmet needs and resentment—we get into trouble. We have to start at home, with ourselves—and this is difficult. Weathering conflict and confrontation in the private sphere is scary, as Harriet Lerner confirms, because it might be the first time we’ve asserted needs and established boundaries when we’ve always been told that doing so is selfish.

We have every right to believe that this bid for reciprocity might make us less lovable, or less “useful,” to our partners—that they might, in fact, revolt or retaliate, and that new lines might need to be drawn. It is here that we find a Venn diagram of overlapping private and public constraints: Many women are practically bound to the patriarchy, through marriage, employment, and family. Asserting any autonomy and self-definition can feel like placing oneself under existential threat.

As Rebecca Traister writes, “Women’s challenge to male authority or power abuse can send a family into disarray, end a marriage, provoke a firing, either of a woman or of a man on whom other women—colleagues and family members—rely economically. Fear[s] of these repercussions (alongside a long-ingrained and realistic fear of simple futility) are very often fierce enough to inoculate women against expressing, and perhaps in many cases even feeling, the outrage at men that they might otherwise make known.” Whether consciously or not, many women are stuck….

METABOLIZING OUR ANGER—AND MOVING PAST AFFIRMATION

White women, in particular, self-flagellate, prostrate ourselves, and resign from jobs at any suggestion of wrongness or badness. We turn our venom on each other and lick wounds, rather than confront our feelings, take empathic accountability, or figure out the most effective path forward. In our frustration and fear, we struggle to own our participation in past behavior or even to acknowledge that change is part of the process.

We aim for perfection, shuddering at the moments when we’ve said the wrong thing, missed an opportunity, put our foot in our mouth. When this happens, many

women (especially white women) get scared—and we stop engaging.

We struggle to move forward because we spend too much time defending our “goodness,” stuck in the binary that if you’re not impeccable in your behavior—across the arc of time—then youvmust be bad. And badness, of course, means you’re undeserving of love; you’ll be cast out of your community, canceled by the culture. This is happening—canceling, silencing—in part because we are

allowing it. We are not going to be perfect. There are no hurdles to clear, no lists to check off. It’s a process that requires a willingness to engage, learn, evolve, and repeat. We can’t skip steps to perfection or doneness. Fear keeps us out of these conversations, prevents us from sharing thoughts or ideas, stops us from asking questions orvshowing up.

Perhaps, to quote professor Dolly Chugh, author of The Person You Mean to Be, instead of gunning to be perfect in our goodness, we should aim for “good enough.”

From On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins & The Price Women Pay for Being Good

Read this book!!

Photo Credit: Valerie Jarvis

This article is intended for informational purposes and is not intended to replace a one-on-one medical consultation with a professional. Wile, Inc researches and shares information and advice from our own research and advisors. We encourage every woman to research, ask questions and speak to a trusted health care professional to make her own best decisions.